Plac Kazimierza Wielkiego został wymazany z mapy Warszawy. Tam, gdzie kiedyś było targowisko, a przez pierwszą połowę XX wieku stała potężna hala targowa, po drugiej wojnie światowej wyrósł Dom Słowa Polskiego.

Dziś w miejscu placu, gdzie jeszcze niedawno wznosiły się zabudowania pofabryczne mieszczące centrum handlowe Jupiter już niedługo będzie nowoczesny, otwarty i wielofunkcyjny kwartał atrakcyjnego miasta, budowany przez Echo Investment i AFI Europe. O tym, że kiedyś był tu plac miejski, mało kto pamięta. Wytyczono go w 1868 r. pomiędzy ulicami Pańską, Wronią, Srebrną i Miedzianą w miejscu parcelowanych ogrodów.

Symbolem tych lat był ówczesny prezydent miasta Kalikst Witkowski. Jego imieniem nazwano nie tylko plac, ale też dzisiejszą ul. Śniadeckich, do 1914 r. – ulicę Kaliksta. Zaborcze władze rosyjskie miały powody do uhonorowania urzędnika. Generał Kalikst Witkowski oddał spore zasługi carowi. Na jego pomniku nagrobnym kamieniarz wyrył liczne odznaczenia, wśród nich ordery przyznane za tłumienie powstania węgierskiego w 1848 r.

Konkurs na budowę hal został rozpisany w 1904 r. W komisji znalazło się dwóch rosyjskich inżynierów wojskowych oraz znani architekci warszawscy: Bronisław Brochwicz Rogóyski, Władysław Marconi i Józef Pius Dziekoński. Nadesłane zostały cztery projekty. Do realizacji wybrano ten autorstwa Henryka Gaya.

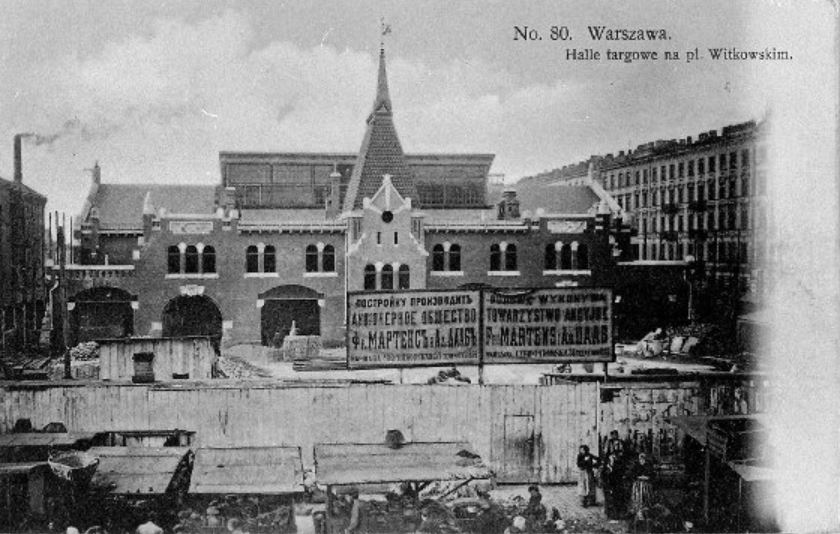

Była to hala o pięciu przęsłach. Prace budowlane prowadziła znana warszawska firma Fryderyk Martens i Adolf Daab. Wykonawcą konstrukcji było Towarzystwo Akcyjne Borman i Szwede, zaś okuć, krat, okien, drzwi i całej „galanterii” żelaznej firma K. Zieleziński. Budowa trwała trzy lata i pochłonęła 450 tys. rubli. Oficjalnego otwarcia hal dokonał 26 listopada 1908 r. ówczesny prezydent miasta Wiktor Litwiński.

Hale przy placu Kazimierza Wielkiego (jak przemianowany Plac po I w. św.) miały ceglane elewacje w duchu zmodernizowanego romanizmu i gotyku. Fasadę budynku frontowego ozdobiła umieszczona na osi wieża zwieńczona stromym dachem z iglicą. W ścianach szczytowych umieszczono wielkie, półkoliste okna. Elewacje ozdobiły rzeźby oraz płaskorzeźby odkute w kamieniu przez Zygmunta Otto. Wiązały się one tematycznie z przeznaczeniem hali jako miejsca handlu artykułami spożywczymi. Wyobrażały ptactwo, ryby, zwierzynę, raki oraz „udatne sceny rodzajowe”. Do budynku wiodły cztery wejścia. Halę wyposażono w nowoczesne urządzenia techniczne: jatki z sufitem kratowanym, kanalizacją i żaluzjami.

Budowla dotrwała do 1944 r. Oglądamy ją m.in. na zdjęciach filmowych, wykorzystanych niedawno w kolorowanym filmie „Powstanie Warszawskie”. Ceglane mury krzepko się jeszcze trzymają, zamykając perspektywę ul. Siennej, której wylot na Miedzianą i plac Kazimierza przegrodzony był barykadą. Kilka miesięcy później hala też nie była kompletną ruiną. Znaczne partie murów i konstrukcji ocalały, można były podjąć jej odbudowę. Tak się nie stało. Podjęto zaskakującą i trudną do zrozumienia decyzję likwidacji placu miejskiego wraz z fragmentami otaczających go ulic i przeznaczenia go pod obiekt przemysłowy.

Źródło: Gazeta Wyborcza

Pierwsze dwa zdjęcia to sam Plac Kazimierza Wielkiego z halą targową, kolejne to kadr z filmu „Powstanie Warszawskie” i porównanie z dnia dzisiejszego (źródło GW). Ostatnie dwa to Google Earth i usytuowanie Placu z halą w przedwojennej tkance oraz w dzisiejszym układzie architektonicznym.

Kazimierz Wielki Square was erased from the map of Warsaw. Where there used to be a marketplace and a huge market hall stood during the first half of the 20th century, after World War II the House of the Polish Word (Poligraphy) was built.

Today former factory buildings housing the Jupiter shopping center are giving place to modern, open and multi functional city quarter being built by Echo Investment and AFI Europe. Few people remember that there was once a city square here. It was marked out in 1868 between Pańska, Wronia, Srebrna and Miedziana streets in the place of plotted gardens.

The symbol of these years was the then mayor of the city, Kalikst Witkowski. Not only the square, but also today’s street was named after him. Śniadeckich, until 1914 – Kaliksta Street. The occupying Russian authorities had reasons to honor the official. General Kalikst Witkowski rendered considerable service to the tsar. The stonemason engraved numerous decorations on his tombstone, including orders awarded for suppressing the Hungarian uprising in 1848.

A competition for the construction of the halls was announced in 1904. The commission included two Russian military engineers and famous Warsaw architects: Bronisław Brochwicz Rogóyski, Władysław Marconi and Józef Pius Dziekoński. Four projects were submitted. The one by Henryk Gay was chosen for implementation.

It was a hall with five bays. The construction works were carried out by the famous Warsaw company Fryderyk Martens and Adolf Daab. The contractor for the structure was Towarzystwo Akcyjne Borman i Szwede, and the fittings, grates, windows, doors and all iron accessories were made by K. Zieleziński. Construction took three years and cost PLN 450,000. rubles. The halls were officially opened on November 26, 1908, by the then mayor of the city, Wiktor Litwiński.

The halls at Casimir the Great Square (as the Square was renamed after the 1st century) had brick facades in the spirit of modernized Romanism and Gothic. The facade of the front building was decorated with a tower placed on an axis, topped with a steep roof with a spire. There are large, semicircular windows in the gable walls. The facades were decorated with sculptures and bas-reliefs carved in stone by Zygmunt Otto. They were thematically related to the purpose of the hall as a place for selling food products. They depicted birds, fish, game, crayfish and „successful genre scenes”. There were four entrances to the building. The hall is equipped with modern technical equipment: slaughterhouses with grated ceilings, sewage systems and blinds.

The building survived until 1944. We can see it, among others: in film photos recently used in the colorized film „Warsaw Uprising”. The brick walls are still standing, blocking the perspective of the street. Sienna, the exit to Miedziana and Kazimierza Square was blocked by a barricade. A few months later, the hall was not a complete ruin either. Significant parts of the walls and structures survived and could be rebuilt. That didn’t happen. A surprising and difficult to understand decision was made to liquidate the city square and parts of the surrounding streets and use it for an industrial facility.

The first two photos are Kazimierz Wielki Square itself with the market hall, the next are a frame from the film „Warsaw Uprising” and a comparison from today (source GW). The last two are Google Earth and the location of the Square with the hall in the pre-war tissue and in today’s architectural layout.